Charles-François Daubigny. 1817-1878

La Machine hydraulique (The Hydraulic Machine). 1862. Original cliché-verre. Delteil, Melot 147. Delteil 147. 8 3/8 x 13 1/2 (sheet 11 x 14). Edition 150, #85. Posthumous impression from the 1921 edition of 150 printed in Paris by Sagot-Le Garrec on photo-sensitive vellum paper, with their violet seal verso (Lugt 1766a). Signed in the plate. A fascinating historical image. $500

![]()

Benoît Fourneyron (October 31, 1802 - July 31, 1867) was a French engineer, born in Saint-Étienne, Loire. Fourneyron made significant contributions to the development of water turbines. He was educated at the École Nationale Supeérieure des Mines de Saint-Étienne, a nearby engineering school that had recently opened. After he graduated in 1816, he spent the next few years in mines and ironworks. Around this time, a number of French engineers, including some of Fourneyron's former teachers—were starting to apply the mathematical techniques of modern science to the ancient mechanism called the waterwheel.

For centuries, waterwheels had been used to convert the energy of streams into mechanical power, mostly for milling grain. But the new machines of the Industrial Revolution required more power, and by the 1820s there was enormous interest in making waterwheels more efficient.

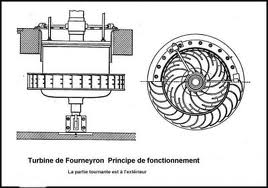

Using the proposal of a former teacher (Claude Burdin) as a guide, Fourneyron built in 1827, at age of 25, his first prototype for a new type of waterwheel, called a "turbine". (The term turbine is derived from the Latin word for a spinning top). In Fourneyron's design, the wheel was horizontal, unlike the vertical wheels in traditional waterwheels. This 6 horsepower (4.5 kW) turbine used two sets of blades, curved in opposite directions, to get as much power as possible from the water's motion. Fourneyron won a 6,000 franc prize offered by the French Society for the Encouragement of Industry for the development of the first commercial hydraulic turbine.

Over the next decade, Fourneyron built bigger and better turbines, learning from his mistakes after each new model. By 1837, Fourneyron had produced a turbine capable of 2,300 revolutions per minute, 80 percent efficiency, and 60 horsepower, with a wheel a foot in diameter and weighing only 40 pounds (18 kilograms). Besides its more obvious advantages over the waterwheel, Fourneyron's turbine could be installed as a horizontal wheel with a vertical shaft. It achieved immediate international success, powering industry in continental Europe and in the United States, notably the New England textile industry. But the real significance of the invention did not emerge until 1895, when Fourneyron turbines were installed on the American side of Niagara Falls to turn generators for electric-power production.

Fourneyron perceived the potential of steam-driven turbines, but his attempts to make a satisfactory steam turbine were thwarted by the inadequacy of available materials and workmanship.

![]()

![]()

To order, to report broken links or to be placed on the email list, please contact Jane Allinson (jane@allinsongallery.com), call (001) 860 429 2322 or fax (001) 860 429 2825. Business hours are 9:A.M. to 5 P.M. Eastern Standard Time.

Please click here to review the USE AND ACCEPTANCE AND PRIVACY POLICIES FOR THE ALLINSON GALLERY, INC. WEBSITE

Thank you for visiting this website.